The ACOG is a time tested optic… however it is getting rapidly displaced by the LPVO in civilian and military circles. This is a guide to share some of the advantages and disadvantages of the ACOG sighting system and compare it to the typical LPVO. Both the LPVO and ACOG are excellent tools for the rifleman, each with its unique advantages and disadvantages. I am going to highlight some thoughts on the ACOG as it relates to a rifleman trying to decide if the ACOG offers him or her anything over the LPVO. This guide will break down a few reasons why the ACOG is still pertinent, and then discuss the advantages (and some disadvantages) for the rifleman the ACOG can provide. Let’s get started!

Weight:

ACOG’s are lightweight. The compact prismatic design and simple construction lead to a compact, lightweight optic. My Ta01 weighs 9 oz and with mount, it runs a portly 14 oz. A Burris RT-6 weighs in at 17.4 oz without the mount. When you add the once piece mount you are adding about 5 more oz to the setup so at a bare minimum you are going to push 20+ oz. To be fair, a variable does allow us to go down to 1x so we need to add an RMR into the equation to give the ACOG the same capability. So let’s add 2.8 oz for the RMR and mount. That brings us to 16.8 oz for a 1x / 4x optic with the mount to compare with a Burris RT-6 which pushes 20 oz with mount. At least.

Simple. Lightweight. Rugged.

The ACOG is a great choice for weight-conscious shooters, especially for shooters running 20-inch cannons. I ran a RAZOR HDII on my 20-inch gun for fun once… and I took it off immediately. The extra weight of a variable is a nicer pairing with a lighter carbine. If weight is a consideration, the rifleman can obtain a robust, lightweight optic that allows him/her to reach out and connect out to 600 yards without the weight penalty of variables and traditional optics.

Low Light Shooting:

Look Ma! No Batteries!

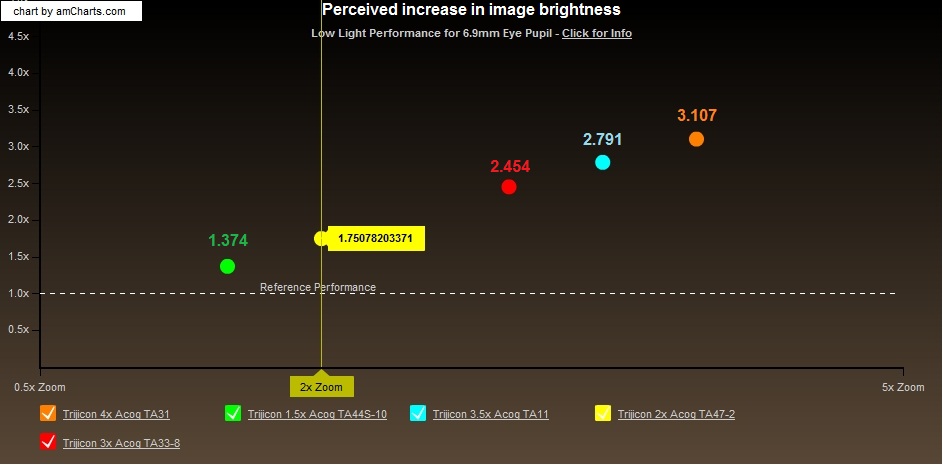

The larger objective lens of the ACOG comes in handy during dim light conditions. When the human eye has had around 20 minutes of dim lighting conditions, the pupil will expand up to 7-8mm to send as much light as possible to the retina. The ACOG’s 32mm objective lens funnels a comparatively large amount of ambient light down to an 8mm exit pupil which matches the pupil diameter the night-adapted eye. The typical 24 mm objective of a variable has much less light-gathering capability in comparison… and it won’t be as efficient until around 3x magnification. The ACOG has a 33 percent larger objective than a typical 24mm variable.

The tritium comes into play as well. Many shooters scoff at the cost and effort to send the optic every 15 years for a recharge… meanwhile the variable needs a fresh 2032 and it’s ready to go. This is true… there have been quotes from Trijicon for 500 dollars for a recharge, but this typically involves new seals, tritium, inspection, and amounts to an oil change for your optic. I have heard that they will drop in new reticles if requested during this procedure! I certainly don’t mind the full reticle illumination of my TA01. Many variables can illuminate their entire reticle, but at the cost of light spillage out the front of the optic. Trying to hide in the dark? Better keep that reticle on low.

Light Bleed from an illuminated variable optic

So as a whole, the ACOG will outclass variables in lower light conditions. While some variables have great light transmission and reticles which don’t flood out the front of the optic (such as the Razor HD) they still can’t match the larger objective lens of the ACOG 4x and 3.5x series of optics. To take advantage of the enhanced light transmission, variables must also be set to a magnification that matches the diameter of the night-adapted eye. This is another step that needs to be taken to enhance dim light shooting that the ACOG user needs not to worry about.

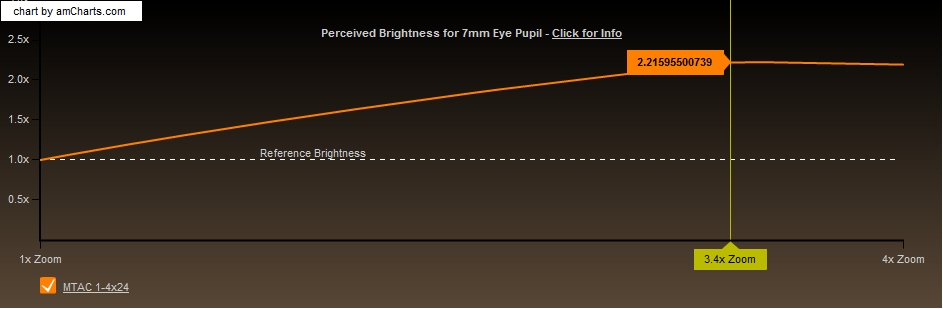

The perceived brightness of a variable depends on the magnification setting of the optic. At 1x there will be no perceived brightness enhancement. The image on an MTAC will be brightest at 3.4x zoom.

A large objective isn’t night vision, but it’s likely as close as you can get with the naked eye.

The 4x ACOG (in orange) offers a perceived 3x brightness enhancement over its peers.

Hit Percentage: What do we give up to 6x-10x?

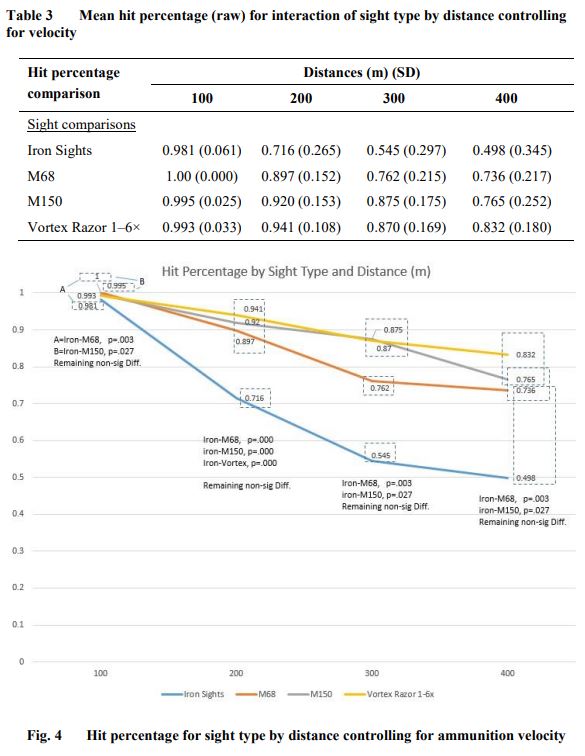

The next point of discussion is the hit percentage. Does the ACOG limit shooters with its 4X magnification? What does it give up to variables? It does give up a little, but overall the 4x magnification doesn’t limit the shooter as much as you would think… at least with the data we have available.

As the above figure above shows, the ACOG (m150) trends closely with the Razor 1-6 until 400 meters. With the additional magnification a variable provides, I am sure it explains the hit percentage improvement. At 300 yards the shooters managed to score about evenly with the Razor HD and ACOG… within the margin of error. The blue line, representing iron sights, is substantially lower in hit probability. Past the studies 400 yards, I am sure the 4x will limit the ACOGs hit percentage as range increases. Balance this with your perceived needs. Weight vs more magnification is the real hand at play here.

The DOWNSIDES:

So while weight, low light performance, and robust housing are in the ACOG’s favor, there are some downsides. Let’s take a gander at some of the big ones that often come up in online discussion.

ACOG’s are Pricey:

The elephant in the room is the cost of the ACOG. Starting at $900 for a basic TA01, it takes a huge financial leap to grab an ACOG for most shooters. If you own an ACOG or variable over 600 dollars than you are a shooting enthusiast. Flat out, the general public has no interest in spending anywhere near that much money on a rifle optic. To compare costs, we need to set a bar for what is an equivalent product in the variable market. Razor HD IIs come to mind as they are comparable in price, durability, and feature a daylight bright reticle. To hash out which is better requires a careful weighing of shooter priorities. Weight. Durability. Enhanced target fidelity. FOV. It’s going to amount to rifleman’s preference as high-end variables and ACOG’s are both excellent sighting systems. So I would count this as a wash. If you’re in the market for a $1000 optic, you can weigh your decision based on your use case. 99 percent of gun owners are not in the market for a 1000 dollar optic.

ACOG’s BAC is WONKY:

The Bindon Aiming Concept is a well-known method of “snap shooting” with the ACOG. It’s just hard to explain to shooters. It’s also nowhere near as precise as a 1X variable. I played with BAC and found it to be suitable for close range, across the room shooting. My hits were solid and it wasn’t hard… but you need experience behind the gun to rapidly mount the rifle and rapidly peer through the ACOG. Good muscle memory and good presentation of the rifle are essential to use BAC effectively. Upon mounting, the bright reticle of the dual illuminated ACOG appears as a streak on the target. The shooter must then fire before the brain takes over the brighter, clearer, 4x image. It requires practice and speed. It is not as duh intuitive as a 1x Variable.

The above diagram is as best as I can relay how things look when using BAC. In real life, in bright light, the reticle appears nuclear bright so that aspect of the photo is misleading. The brain wants to “focus” on the bright, crisp ACOG sight picture while the other eye focuses on the target. If you delay then you will mentally focus on the 4x image and this isn’t ideal. Snap fire upon seeing the reticle on target is the proper order to use BAC.

However, it is 2020. We mount RMR’s on everything. The BAC feature became less important as we can now mount a 1x optic piggybacked on the ACOG. Is this as desirable as 1x on a variable? Not really, but it does allow the shooter both a backup sight should the ACOG fail and can be used for snap fire with less drama than BAC. On a side note, anyone notice that even Razor HD IIs are getting RMR mount rings?

“Yo Dog I heard you like 1x optics for yo 1x optic so I got you this mount that lets you 1x your 1x.” Reptilla RMR Mount

The above setup has had some positive feedback from hardcore shooters so there is still merit to a 1x optic high overbore… even when you can yank your variable down to 1x. Passive night vision use comes to mind. FUTURE READY.

So BAC is wonky, but for additional funds, you can work around the poor performance of BAC and grab an RMR for up-close shooting.

But MUH Eye Relief !

This is a “problem” on 4x models as they have the worst eye relief of the Trijicon ACOG lineup. As a hardcore iron sight shooter, I have no problem getting behind the glass of an ACOG. Proper mounting of the ACOG is essential. Adjustable stocks help alleviate eye relief issues as the ACOG can be mounted mid-way down the receiver and the stock can then be adjusted to make the rifleman comfortable behind the gun. Many new ACOG owners mount the ACOG at the rear of the upper receiver to obtain comfortable eye relief, but the solution is getting the gun setup where rifle ergonomics match the shooter. A2 stock owners notwithstanding… not much you can do there.

So while the short eye-relief is an often-discussed issue, I have never had a problem with 4x ACOGs. A properly set up rifle will allow comfortable shooting from all positions with the 4x ACOG. Muscle memory, proper rifle setup, and solid shooting fundamentals will negate the eye-relief issues.

Wrapping Up Until Part 2:

Wew that’s kinda a long article. So we have discussed some of the advantages and disadvantages of the ACOG. It’s a lightweight, robust optic that can go toe to toe with modern variables provided you can weigh the advantages and disadvantages. I will be writing part 2 to cover ACOG models, reticle choices, loadings, and parallax errors with the ACOG. It’s gonna be fun, so expect a drop as my next big article. Until then, look for more stuff from Richard and Damien!

MAH FAVORITE ACOG PICTURE. I MADE DIS. LOTHAEN OUT.

I really appreciate this article on the ACOG. I recently came into possession of a random ACOG and have run into a few roadblocks in discerning which model/features/reticule I have. There does not seem to be one, single definitive source for info about them on the internet. As it happens, I was about to purchase a LPVO immediately prior to the ACOG coming into my possession, and am now trying to decide the best course of action. This article has been very helpful and I am looking forward to part two.

Thanks for the thoughts Mutt. If you randomly get anymore random ACOGs let me know mkay? 🙂